Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

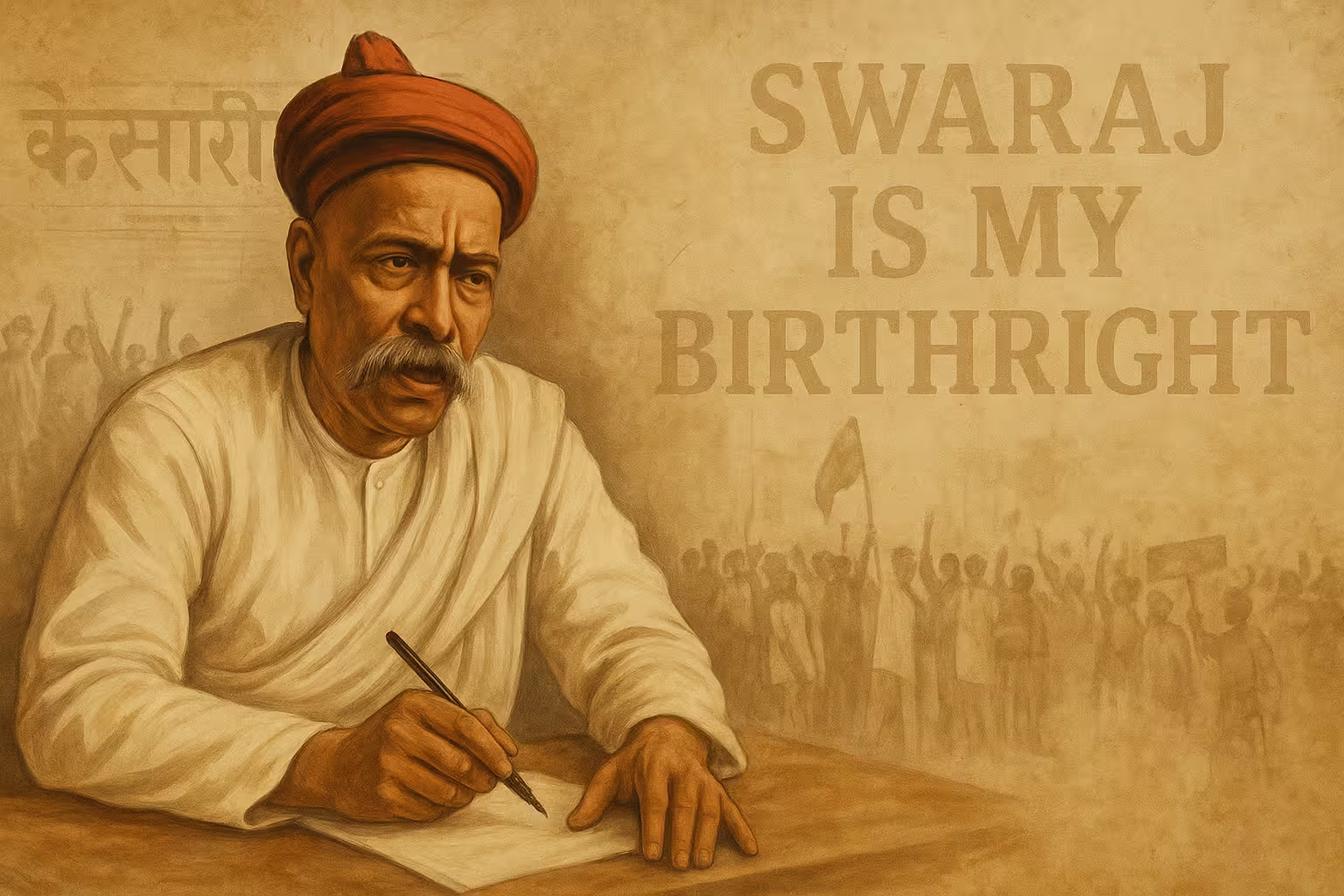

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, popularly known as Lokmanya Tilak, was one of the foremost leaders of the Indian independence movement. A scholar, reformer, journalist, and political leader, Tilak played a pivotal role in awakening national consciousness among Indians during the British colonial era. With the clarion call of “Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it,” Tilak ignited a spirit of patriotism that shaped the trajectory of India’s struggle for freedom. This article presents a comprehensive biography of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, exploring his early life, education, political ideology, journalistic contributions, social reforms, religious beliefs, and enduring legacy.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was born on 23rd July 1856 in Ratnagiri, a coastal town in present-day Maharashtra. He belonged to a Chitpavan Brahmin family and was deeply influenced by a traditional yet intellectually enriched household. His father, Gangadhar Ramchandra Tilak, was a schoolteacher and a Sanskrit scholar. The family later moved to Pune, a city that would eventually become the center of Tilak’s educational, political, and journalistic activities.

Tilak was a brilliant student with a strong inclination toward mathematics and Sanskrit. He completed his matriculation from Poona High School and pursued higher education at Deccan College. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in Mathematics in 1877 and later completed a degree in law from Government Law College, Bombay, in 1879.

However, Tilak’s educational journey was not confined to academic achievements. He harbored a deep interest in Indian history, culture, and religion. He was critical of the British education system, which he felt alienated Indians from their cultural roots. Tilak’s academic background and nationalistic fervor laid the foundation for his multifaceted career.

Read Also: Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, life story, contributions, movements, ideals

One of Tilak’s earliest contributions to Indian society was in the field of education. He co-founded the Deccan Education Society in 1884 along with his associates Vishnushastri Chiplunkar and Gopal Ganesh Agarkar. The objective was to promote Indian-controlled education that instilled national pride among students.

In 1881, Tilak started two newspapers: Kesari in Marathi and The Mahratta in English. These publications became powerful tools for spreading nationalist ideas. Kesari especially reached the masses and exposed the oppressive policies of the British Raj. His bold editorials led to multiple sedition charges by the British authorities, but they also made him a household name in India.

Tilak believed that India needed a cultural resurgence to counter colonial subjugation. He was instrumental in popularizing public celebrations of Ganesh Chaturthi and Shivaji Jayanti. These festivals became platforms for promoting unity, national pride, and social cohesion.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Tilak advocated for a return to Indian traditions while embracing modern reforms where necessary. He believed in the spiritual and moral rejuvenation of Indian society, which he considered a precondition for political freedom.

Tilak entered mainstream politics in the late 19th century through the Indian National Congress. However, he soon emerged as a leader of the extremist faction, as opposed to the moderates led by Gopal Krishna Gokhale. Tilak championed direct action and mass agitation rather than constitutional methods alone.

He was part of the iconic “Lal-Bal-Pal” trio, along with Lala Lajpat Rai and Bipin Chandra Pal, which symbolized assertive nationalism. Tilak’s philosophy was deeply rooted in self-reliance, civil liberties, and a cultural assertion of Indian identity. His vision of Swaraj (self-rule) went beyond mere political autonomy; it represented the total emancipation of the Indian spirit.

Tilak played a critical role in the Swadeshi Movement that emerged in response to the partition of Bengal in 1905. He urged people to boycott British goods and promote Indian industries. He also advocated for national education, self-governance, and indigenous enterprise. His writings and speeches energized the youth and awakened the masses from colonial apathy.

Tilak’s nationalism was inclusive but deeply rooted in Hindu philosophy. He interpreted the Bhagavad Gita as a text of action and duty, encouraging Indians to resist oppression through righteous struggle. His philosophical outlook combined dharma with patriotism.

In 1908, Tilak was arrested on charges of sedition for his alleged support of revolutionary activities. He was sentenced to six years of rigorous imprisonment and was deported to Mandalay jail in Burma (present-day Myanmar).

During his incarceration, Tilak wrote one of his most influential works, Gita Rahasya (The Secret of the Gita), in which he presented the Bhagavad Gita as a guide to selfless action and spiritual courage. The book remains a seminal work in Indian political and spiritual literature.

Upon his release in 1914, Tilak returned to the political arena with renewed vigor. In 1916, he launched the Home Rule Movement along with the Irish theosophist and reformer Annie Besant. The movement demanded self-government within the British Empire and mobilized people across linguistic, religious, and regional boundaries.

The Home Rule Movement marked Tilak’s transition from a regional leader to a national icon. His pragmatic collaboration with Besant and others showcased his ability to unify diverse forces under the common cause of Swaraj.

Although both Tilak and Gandhi aimed for India’s freedom, they differed in approach. Tilak believed in assertive action and did not hesitate to confront British authorities, while Gandhi emphasized non-violence and civil disobedience. Nevertheless, Gandhi acknowledged Tilak as a great leader, and Tilak’s groundwork laid a strong foundation for later movements led by Gandhi and others.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak passed away on 1st August 1920 in Mumbai. His death was mourned across the nation, with thousands attending his funeral. Mahatma Gandhi, paying tribute to Tilak, said, “He was the maker of modern India.”

Tilak’s passing marked the end of an era in Indian politics but his legacy continued to inspire future generations. His ideas on Swaraj, Swadeshi, and education became cornerstones of India’s freedom movement.

Tilak’s legacy is vast and multifaceted. He was a bridge between traditional Indian values and modern political activism. His emphasis on cultural nationalism inspired numerous leaders, from Subhas Chandra Bose to Veer Savarkar.

Educational institutions, public monuments, and awards in his name continue to honor his contributions. The Lokmanya Tilak National Award, given annually to distinguished personalities in various fields, keeps his memory alive.

Tilak’s impact on journalism, education, religious interpretation, and political mobilization remains unparalleled. He gave a voice to the voiceless and turned festivals into forums for national awakening.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was much more than a political leader; he was a visionary who foresaw the need for a spiritually and culturally awakened nation. His bold stance against colonial oppression, his efforts in building indigenous institutions, and his emphasis on self-rule left an indelible mark on India’s freedom struggle.

By blending tradition with modernity, action with wisdom, and nationalism with ethical values, Tilak laid the foundation for a sovereign India. His life remains a testament to the power of conviction, the strength of ideas, and the enduring spirit of patriotism.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak truly earned the title “Lokmanya”—approved and loved by the people. His legacy continues to inspire, reminding us that the road to freedom begins with self-belief and a relentless pursuit of justice.

Read Also: What Is in the First Chapter of the Bhagavad Gita? – Arjuna Vishada Yoga