Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

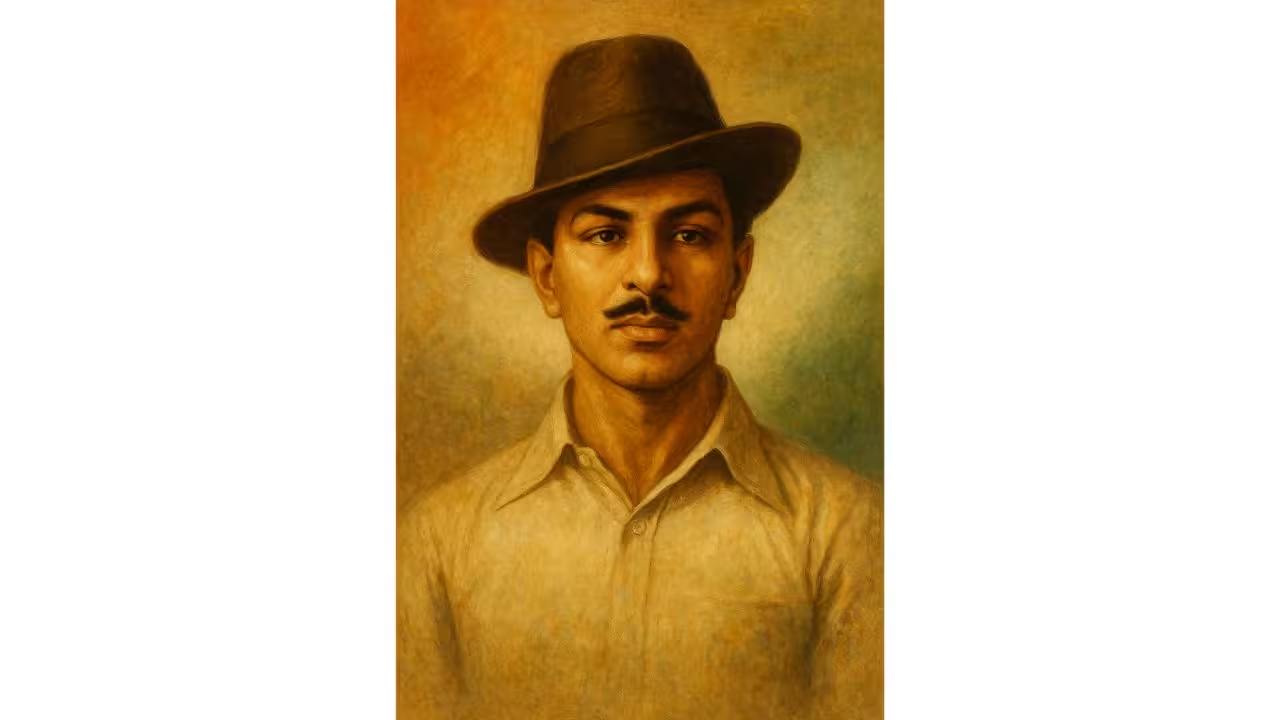

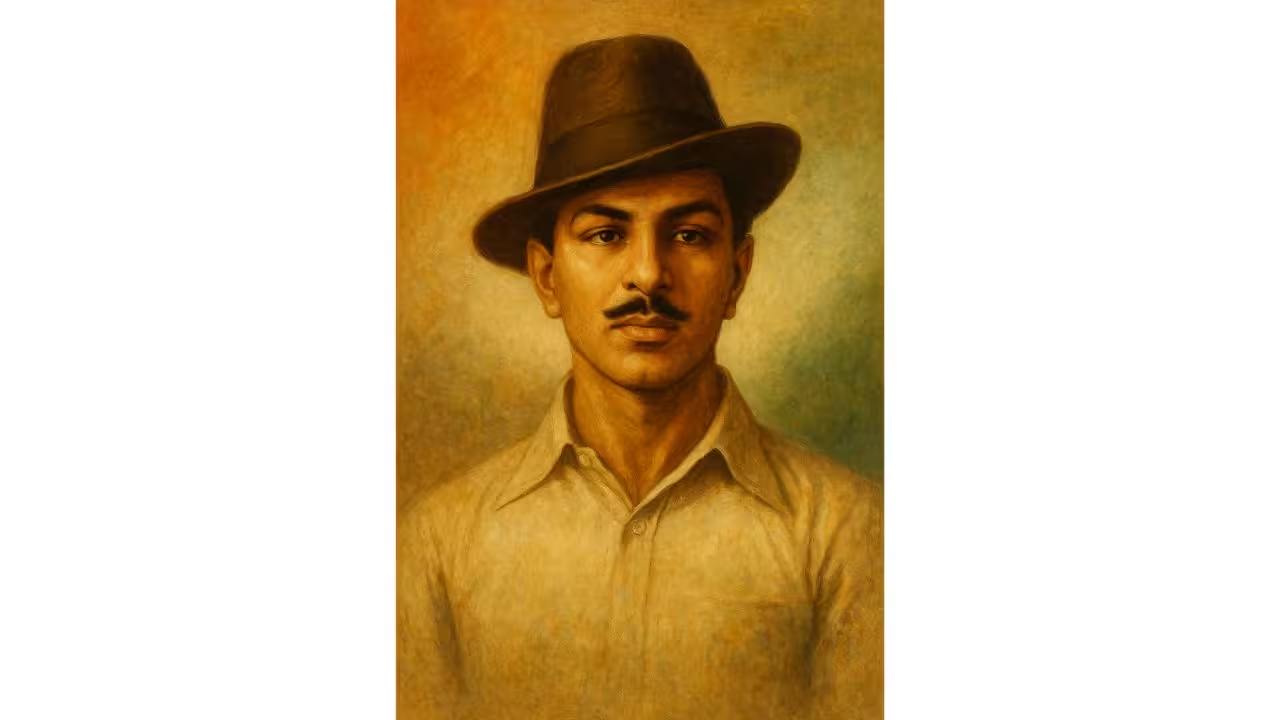

Bhagat Singh (1907–1931) remains one of India’s most compelling symbols of youthful courage, revolutionary idealism, and intellectual clarity. Often remembered as Shaheed‑e‑Azam (the great martyr), he combined a razor‑sharp political mind with extraordinary personal courage. His ideas were not impulsive outbursts; they were honed through deep reading, disciplined debate, and uncompromising ethical choices. This comprehensive, SEO‑friendly biography presents Bhagat Singh’s life from his early years in Punjab to his execution on March 23, 1931, clarifying events, dates, organizations, and writings with care so that students, researchers, and general readers find an accurate and engaging resource.

Bhagat Singh was born on September 27 or 28, 1907, in Banga village (Jaranwala Tehsil, Lyallpur—now Faisalabad, Pakistan), in the then Punjab of British India.[1] He came from a Sikh family steeped in patriotic fervor. His father Kishan Singh and uncles Ajit Singh and Swaran Singh were known for their opposition to colonial rule, and this atmosphere of resistance shaped the young Bhagat’s worldview. His mother, Vidyavati, nurtured him with deep affection and moral strength. The household’s discussions on politics, sacrifice, and national dignity were not abstract to him; they were the very air he breathed.

Growing up in an agrarian setting but close to Lahore—the intellectual and political hub of the region—Bhagat Singh witnessed the tensions of colonial agrarian policies, censorship, and police surveillance. Stories of earlier revolutionaries and the legacy of movements like the Ghadar Party circulated widely in Punjab, encouraging critical questions about justice and the path to freedom.

Bhagat Singh studied at institutions that prized both modern education and Indian cultural pride. He attended the Dayanand Anglo‑Vedic (DAV) High School in Lahore, where he was exposed to nationalist ideas and rigorous discipline. Later he enrolled at the National College, Lahore (founded in 1921 by Lala Lajpat Rai), an institution created explicitly to nurture self‑respecting, politically aware youth outside the tight control of colonial curricula. Here, he studied history and political theory, took part in dramatic societies, and sharpened his writing skills.

One decisive influence was the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of April 13, 1919, in Amritsar. As a boy barely in his teens, Bhagat Singh visited the site soon after the tragedy and collected soil soaked in the blood of innocents as a relic—a powerful symbol for him of the moral urgency of freedom. The event seared into his consciousness the reality of colonial violence and the insufficiency, in his view, of purely petitionary politics.[2]

The early 1920s were marked by the Non‑Cooperation Movement under Mahatma Gandhi. When Gandhi suspended the movement in February 1922 following the Chauri Chaura incident, many young nationalists, including Bhagat Singh, felt a profound disappointment. Yet this was not a turn to nihilism for him. Instead, he deepened his study of revolutionary histories and philosophies, exploring the Irish and Russian experiences and reading widely on socialism, anarchism, and anti‑imperial thought.

As a student and young organizer in Lahore, he wrote for and edited publications sympathetic to revolutionary programs, refined his skills in clandestine work, and learned to prioritize organization over spectacle. He understood early that spontaneous anger, unless disciplined by strategy and ideas, could be wasted energy.

Bhagat Singh Book : Why I am an Atheist and Other Works | Letters & Jail Diary of Bhagat Singh on Revolution, Religion & Politics

In March 1926, Bhagat Singh founded the Naujawan Bharat Sabha in Lahore to mobilize youth for a secular, egalitarian, and fearless vision of India.[3][4] The Sabha emphasized social reform, inter‑communal harmony, and the rejection of superstition alongside the rejection of imperialism—an outlook that later found mature expression in his prison writings.

At the same time, he became closely involved with the Hindustan Republican Association (HRA), which, after internal debates and the impact of global events, evolved into the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) in 1928. The HSRA’s famous meeting at Feroz Shah Kotla (Delhi) articulated a turn from mere nationalist defiance to a clear socialist program: the struggle against colonialism had to be linked with a struggle against feudal and capitalist exploitation.[5] This shift distinguished Bhagat Singh’s politics from narrowly nationalist currents of the time.

In October 1928, Lala Lajpat Rai led a protest against the Simon Commission in Lahore. The police lathi‑charge, ordered by James A. Scott, resulted in serious injuries to Rai, who died on November 17, 1928. The HSRA planned to retaliate against Scott; however, on December 17, 1928, in a case of mistaken identity, Assistant Superintendent of Police John P. Saunders was shot dead.[6] The action team included Shivaram Rajguru and Bhagat Singh as the principal shooters, with Chandrashekhar Azad providing cover, and Jai Gopal involved in reconnaissance. The killing made Bhagat Singh the focus of a massive colonial manhunt.

In its internal debates, the HSRA defended the action as political retaliation against state violence, not personal vendetta. Bhagat Singh shaved his beard and cut his hair to evade arrest—a difficult decision for a devoutly raised Sikh youth, reflecting the scale of risk he was prepared to take for what he considered a larger revolutionary duty.

To protest repressive bills and to dramatize the idea that revolution sought to “make the deaf hear,” Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt carried out a carefully planned, non‑lethal bombing in the Central Legislative Assembly, Delhi, on April 8, 1929. The bombs were designed to create sound and smoke, not casualties. After throwing leaflets that explained the political purpose and aims of the HSRA, the two deliberately courted arrest.[7][8][9]

This act served two goals. First, it moved the struggle from the underground to a public, moral theatre where the courts and the press became new battlegrounds. Second, it allowed Bhagat Singh to foreground the ideological and ethical content of the revolutionary movement—its commitment to the masses, its critique of colonial law, and its aspirations for a just, socialist future.

Following their arrest, Singh and Dutt used the courtroom to challenge the legitimacy of colonial rule and to demand recognition as political prisoners, not common criminals. Conditions in jail for Indian undertrials were notoriously unequal compared with those for European prisoners. In mid‑1929, Bhagat Singh and fellow revolutionaries launched a hunger strike demanding equal treatment—better food, clothing, reading materials, and access to legal counsel.

The hunger strike electrified the country. Jatin (Jatindra Nath) Das died on September 13, 1929, after 63 days of fasting, and his funeral drew massive crowds.[10] Bhagat Singh continued his strike to a remarkable 116 days, forcing the colonial government into negotiations and firmly embedding the revolutionaries in public sympathy.[11] The strike transformed him from a bold revolutionary into a nationwide moral voice.

Read Also : Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, life story, contributions, movements, ideals

Far from being a mere man of action, Bhagat Singh was an articulate thinker. His essays and letters reveal a mind committed to reason, equality, and human dignity. In 1930, while in prison, he wrote the celebrated essay “Why I am an Atheist,” an unsentimental reflection on belief, courage, and ethics. He argued that moral courage demands responsibility for one’s actions without appealing to divine sanction, and that scientific temper is indispensable to modern nationhood.[12][13]

Equally central to his ideology was socialism—a conviction that political freedom without social and economic justice would leave the masses unfree. He read Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and other socialist thinkers, and insisted that the Indian struggle join hands with global movements against exploitation. He supported labor rights, peasant uplift, and inter‑communal solidarity, and argued that caste, communalism, and superstition must be overcome for true freedom.

In letters such as the “Letter to Young Political Workers,” he advised the next generation to study systematically, reject personality cults, and stay vigilant against sectarianism. He emphasized that means must reflect the ends—that a liberatory politics cannot be built on cruelty or opportunism.[14] These writings remain enduring resources for civics education and political ethics in India.

While Singh and Dutt were on trial for the Assembly bombing, the colonial police linked Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar, and Shivaram Rajguru to the Saunders case. A special tribunal tried them in what came to be known as the Lahore Conspiracy Case. The proceedings, criticized by nationalists for procedural shortcuts and bias, ended with the court pronouncing the death sentence on October 7, 1930 for Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev.[1]

Despite petitions and fervent public appeals, the sentence was carried out on the evening of March 23, 1931, at Lahore Central Jail. The colonial authorities reportedly advanced the execution time. Contemporary accounts differ on the exact secret cremation site: several sources state the bodies were taken through a breach in the back wall and hurriedly cremated on the banks of the Sutlej near Ganda Singh Wala (now in Pakistan), while Indian memorial literature places the secret cremation at Hussainiwala (present‑day Punjab, India).[15][16][17][18] Bhagat Singh was only 23 years old.

The execution of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev shook India. March 23 is commemorated as Shaheed Diwas (Martyrs’ Day) in their honor. Over time, Bhagat Singh’s image—often with a felt hat and a calm, unflinching gaze—has become shorthand for integrity, courage, and youthful idealism in public culture. Streets, institutions, and memorials across India keep his name alive. The Hussainiwala National Martyrs Memorial remains a significant site of collective remembrance.[15][16]

Culturally, Bhagat Singh has been depicted in countless films, plays, songs, and biographies. But beyond the icon lies the mind of a disciplined organizer and serious thinker. He stands out not only for spectacular actions but for the coherence of his worldview: anti‑imperialism grounded in social justice, rational inquiry, and the dignity of labor. In a world still wrestling with inequality and authoritarianism, his writings retain sharp contemporary relevance.

Q1. When and where was Bhagat Singh born?

A. He was born on September 27 or 28, 1907, at Banga in Lyallpur (now Faisalabad, Pakistan), then in British India’s Punjab.

Q2. What organizations was he associated with?

A. He founded the Naujawan Bharat Sabha (1926) and became a leading member of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) after the HRA’s reorganization in 1928.

Q3. What was the purpose of the Central Legislative Assembly bombing?

A. It aimed to protest repressive laws and “make the deaf hear”—to broadcast the revolutionaries’ political message with non‑lethal devices and leaflets, not to cause casualties. Singh and Dutt intentionally courted arrest to use the trial as a platform.

Q4. How long did Bhagat Singh’s hunger strike last, and what did it achieve?

A. His strike lasted 116 days in 1929. It highlighted discriminatory jail conditions, won public sympathy, and pressured the government to concede several prisoner‑rights demands.

Q5. What did Bhagat Singh write in prison?

A. Notably “Why I am an Atheist” (1930), along with letters and notes such as the “Letter to Young Political Workers.” His writings advocate scientific temper, socialism, and ethical politics.

Q6. When was he executed and where were his remains cremated?

A. He was executed on March 23, 1931, at Lahore Central Jail. Contemporary accounts differ on the secret cremation site (banks of the Sutlej near Ganda Singh Wala vs Hussainiwala); today, the Hussainiwala National Martyrs’ Memorial is the public site of remembrance.

Q7. Why is Bhagat Singh significant today?

A. He embodies fearless youth leadership coupled with intellectual rigor. His commitment to social justice, rational inquiry, and national dignity offers a timeless guide for democratic citizenship.